Oxford: 30 Unusual Stories Behind the Academic Walls

Oxford feels like a place that dreams with its eyes open. The air tastes of rain and memory, and the cobblestones seem to hum with half told stories. Beneath the formal beauty of its towers and courtyards, there’s a quieter pulse – a mix of curiosity and nostalgia that never quite fades. Wander long enough, and you start to feel it too: the sense that this city keeps its heart tucked inside its history, still beating softly for those who listen.

Where Oxen Crossed, Scholars Learned to Wade

I love when grand places admit their muddy past. Long before spires and Latin murmurs, Oxford was a marshy notch in the river, an oxen ford where cattle pressed through the Thames with tails flicking and hooves pulling at the silt. Even now I can almost hear the wet hush of reeds and the lazy jingle of a bell, and it makes me grin to picture solemn minds sharing a path with patient cows and bookbags brushed with hay.

There’s something tender in that origin, like a library built on hoofprints. It makes the place feel humble in the best way, a reminder that brilliant days are born from practical needs. The air carries a soft dampness that never quite leaves the stones, and I find it oddly comforting to know that wisdom here grew up beside mud, bells, and the steady patience of animals.

So old it forgot its own birthday

It still makes me smile that no one can throw the university a proper birthday party. Lessons were being noted as early as 1096, long before the Magna Carta or the clatter of printing presses. Time here feels steady and wide, like a river that began before maps.

I remember the bell’s slow chime and the smell of rain on old stone, and how it makes those dates feel human. By the time Columbus set sail, its alumni already stretched back centuries; imagine learning by candlelight, words traveling ear to ear because books were scarce, and still that stubborn hunger for ideas. In Oxford, the years don’t need a precise starting line the place holds them gently, and you feel them in the quiet between footsteps.

A college born from an insult and atonement

I love how some histories end more gently than they begin. In the 13th century, John de Balliol offended the Bishop of Durham so badly that his penance was to fund a college for poor scholars. And here’s the twist that makes me grin: they named it Balliol College anyway, an apology carved into stone and syllabus.

Once, after a passing shower, the bell floated over damp stone and the grass smelled newly rinsed; the place felt stern and a little amused. In Oxford, it stands as a reminder that even pride can be turned into opportunity, old quarrels ending in scholarships.

Surprising, isn’t it, that an insult could become shelter for centuries of minds? That kind of justice sticks with me. When I see the name Balliol, I remember that remorse, done right, can change lives.

The riot that ended with yearly pennies

I remember leaning over a sticky pub table, the air warm with malt and old laughter, and someone grumbling about a flat pint. It made me think of how small sparks start big fires: in Oxford, a quarrel over bad beer once swelled into three days of fighting, leaving ninety three people dead. History here feels close enough to fog your glasses; it clings to the rafters like smoke. It’s strange and a little heartbreaking how a taste can tip into rage, and a town can wake up counting its losses.

What stays with me most is the aftermath: every February, for the next four hundred seventy years, the university paid the city a single penny in penance. A coin pressed like a bandage over an old bruise tiny, precise, and tender in its own odd way. I love that about this place: how it can fold remorse into ritual, grief into bookkeeping, as if the rhythm of a calendar can steady a shaken heart. It’s absurd, yes, but also beautiful a reminder that even sour ale can ferment into memory, and memory into a promise to do better, one small coin at a time.

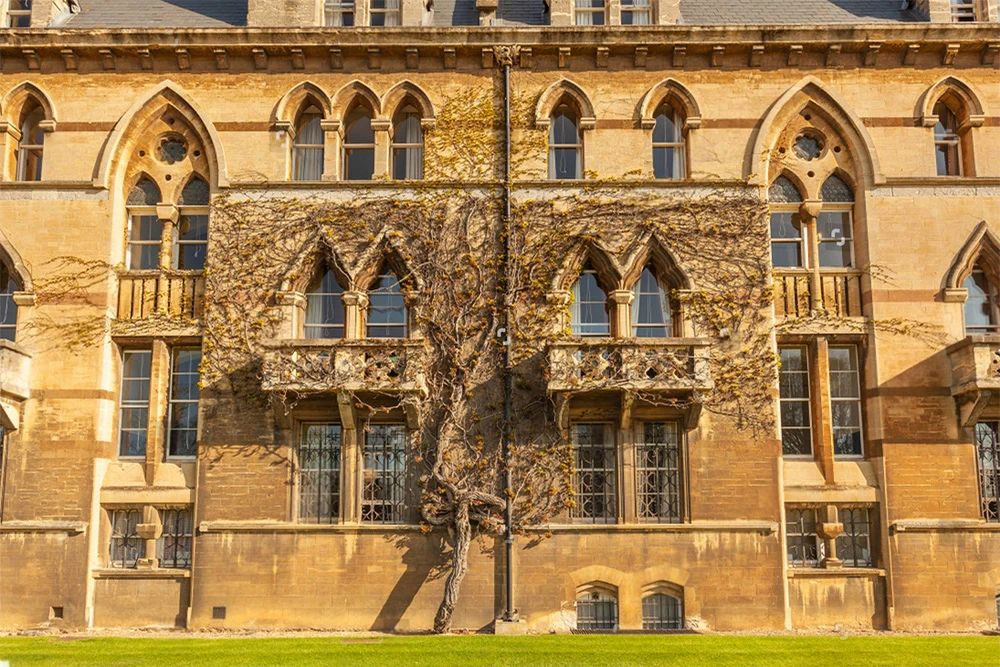

When Oxford Wore England’s Crown for a Moment

It still amazes me that Oxford, a university town, once ran a kingdom for a breath, during the English Civil War. Charles I ran his court from Christ Church, slept within reach of the spires, and called Parliament to gather in Convocation House. I picture candle smoke threading up into the rafters, cold stone underfoot, and quills scratching until midnight; somewhere in those sandstone rooms, choices trembled like an ink line holding its breath.

I think that's what I love about places: they carry contradictions so calmly. The same buildings held both lessons and debates over allegiance; books were opened while armies waited beyond the fields. Standing there, I felt the quiet weight of decisions and the strange tenderness of power how a city built for learning can, for a while, become the center of a country and then return to its usual rhythm.

Rumors threading beneath the cobbles and chapel bells

Sometimes the stones seem to murmur when evening cools the lanes, a damp breath rising from the gaps between cobbles. People say the ground is stitched with tunnels, slipping quietly from colleges to chapels to pubs, like veins under a sleeve. The most delicious whisper? A passage beneath St Edmund Hall where Henry II could meet his mistress unseen, while Queen Eleanor remained none the wiser.

I remember hearing that over a table scarred with initials, the air sweet with malt and old wood. It didn’t feel scandalous so much as tender, the way history sometimes tucks its heartbeat into small doorways. Oxford suddenly felt deeper, like every bell note had a shadow note beneath it, a hidden harmony only the stones could hold.

Whether the passage still exists almost doesn’t matter; it’s the idea that hums underfoot, making you walk softer, as if you might wake the past. Pubs, prayers, lectures, and secrets all sharing the same corridors what a beautiful tangle, a city that keeps its dignity while letting its whispers breathe through the cracks.

A quiet spring where stories choose to linger

Some places feel like they’re holding their breath at the edge of a city. Just beyond Oxford, St. Margaret’s Well sits in a hush, a small stone circle wrapped in shade. The air smells of wet leaves and iron, and the surface trembles now and then. I remember feeling suddenly unhurried, as if time itself had pulled up a chair.

People have come here for centuries with tender wishes, believing the spring could lift the dark from tired eyes or open a door that wouldn’t budge. Locals say Queen Katherine of Aragon once prayed at this very spot, and that detail always gets me – the thought that even a queen might lean on the same hope as anyone else, the same cold edge of stone under her hands. There’s something bracing about that kind of honesty, the way a place can hold both power and vulnerability without fuss.

And then there’s the whimsy threaded through it: Lewis Carroll wandered these parts and turned the well into the “treacle well” of Alice in Wonderland, a sweet joke borrowed from a sacred spring. It makes sense; childhood wonder and old faith often drink from the same cup. Standing there, you can feel how stories cling like dew, and how a quiet pool can make you believe – not just in cures, but in the gentle magic of paying attention.

The spires Hitler supposedly spared for his grand plans

Some cities carry rumors like pocket charms. Walking past honey colored stone still warm from the afternoon sun, I remember hearing the old story that a tyrant earmarked these roofs for his future throne room. Historians shrug, of course, and the bells go on chiming as if to say, don’t be ridiculous.

But wartime memory is a stubborn thing, and the way the Luftwaffe seemed to skirt these spires lets the whisper cling like ivy to the stone. It’s unsettling and oddly tender at the same time this idea that beauty might have been spared not out of mercy, but ambition. You feel it most at dusk, when the air smells faintly of rain and the tower silhouettes look almost too delicate to have survived anything harsher than a gust of wind.

Maybe that’s why the story endures in Oxford: it gives the skyline a fragile kind of defiance. Even if the rumor isn’t true, it reminds you how cities are kept alive not just by luck and strategy, but by the tales people tell to make sense of them. And somehow, knowing the truth is muddy makes the spires gleam a little brighter.

A bell that rings five minutes behind time

Just after nine, the first toll arrives like a slow heartbeat that refuses to hurry. Great Tom at Christ Church in Oxford gathers the dusk into itself, the sound slipping over old stone and bicycle wheels and the faint chill of evening. At 9:05 p.m., it begins its patient count – 101 deep notes, one for each of the college’s first scholars – and the city seems to stand still long enough to listen.

It always makes me smile that it starts late on purpose. This place keeps its own “local time,” five minutes behind everyone else, as if the town is carrying an old key in its pocket and won’t swap it for something shiny and new. There’s something tender about that small defiance: a reminder that clocks can bend to tradition, that not every rhythm has to match the rest of the country.

I remember losing track somewhere around sixty, not out of boredom but because the sound felt like weather, steady and familiar. By the last toll, the day has softened at the edges, and you feel counted, included – as if the bell has taken roll and found room for you, too.

The lawns quietly announce who may cross

I remember pausing at the edge of a quad, the click of shoes on old flagstones and the sweet, sharp scent of cut grass hanging in the air. At Oxford, students flowed along the stone paths while the lawns lay so perfectly trimmed they looked almost untouched. Then a professor stepped off the pavement and crossed the green – no swagger, just a small permission made visible – and suddenly the whole place made sense.

Here, you can read rank by footsteps. Students keep to the edges; professors and dons have the right to cross – they even call it “grass privileges.” It’s not arrogance at all, just the quiet way a university marks its elders, a nod to years spent thinking and teaching. I loved how such a tiny rule holds so much history, reminding you that learning also lives in these unspoken courtesies, the ones that make you slow down and notice the place you’re in.

Exams in Black Ties and Blooming Courage

It catches you off guard in Oxford: a stream of students in black gowns and bow ties, carnations pinned neatly to their lapels, capes brushing at their shoulders. The morning smells of wet stone and paper, and for a second it feels like stepping into another century, the kind where nerves hide beneath starch and ceremony.

I remember glancing at the flowers more than the gowns. They start white on the first day, all clean optimism, then turn pink as the week wears on, a soft little vote of hope. By the end they’re red – survival stitched right to the chest – and you can’t help but root for anyone carrying that final bloom, because everyone knows what it took to earn it.

There’s something tender about fear being translated into petals and tradition. It makes the stress visible and, somehow, gentler, each carnation a small lantern for the heart. For all the theater of it, what stays with me is the quiet courage in those colors – the way a city lets its students wear their feelings openly, and calls it dignity.

Swearing off fire in a house of memory

I didn’t expect a library to feel like ceremony. At the Bodleian you actually swear, aloud, not to bring fire or flame inside the same vow they say has held since “dragons roamed libraries.” The hush has its own gravity, the air cool against the skin, and some part of you quiets as if you’re entering a space that remembers more than you do.

There are more than thirteen million books and manuscripts, yet it behaves less like a warehouse and more like a shrine. I remember my breath thinning, as if I’d stepped into a cathedral of pages; dust motes catch the light, and somewhere a single leaf turns with a whisper you feel more than hear. The vastness doesn’t shout; it leans close and asks you to listen.

That old oath made me smile at first, then feel oddly moved. It isn’t only about banning candles; it’s a small promise that knowledge matters enough to guard it from the oldest kind of danger. In a world that blazes and scrolls by, this place asks for care and slowness, reminding me that words are embers we protect so they can keep warming whoever comes next.

Studying with the quietest classmates

There’s a particular hush that makes your shoulders drop: cool stone, lamplight, and the faint, earthy smell of centuries. Beneath Saint Peter in the East, an 11th century crypt now serves as St Edmund Hall’s reading room in Oxford, where students shape essays while long forgotten clergy rest nearby. I remember feeling strangely welcome, as if the past pulled out a chair and nodded at the stack of books. The names are gone, but the presence is steady.

In that room, the silence folds around you like a wool blanket, and deadlines stop shouting. Bones lie in their niches, a reminder that time stretches like a long corridor of shelves, and we’re just reaching for our little part. It isn’t morbid more like a gentle nudge to be brave with the page. I left with the sense that finishing an essay was a small promise kept to those who kept watch long before us.

An eccentric attic where human hopes share shelves

I remember lowering my voice without meaning to, as if the cases could hear me. The air was warm with old wood and glass, the kind that makes light go soft around the edges. Shrunken heads sat not far from Victorian prosthetics; a witch bottle glinted beside amulets meant to keep curses at bay. It felt less like a gallery and more like stumbling into someone’s lifelong stash of curiosities and questions, each drawer labeled with a worry or wish.

In Oxford, the Pitt Rivers sorts its wonders by what people were trying to do: protect a child, bargain with fate, mend a body, see the invisible. That jumble makes the distances between us collapse; you start noticing the same small fears repeating in different hands and materials. I left with that odd sense of comfort museums rarely give, as if the room itself were a quiet chorus of solutions strange, sincere, sometimes unsettling reminding me we’ve all been trying to keep the same shadows at the door.

Dawn hymns and river splashes on May Morning

There’s always a hush just before the first note, even among the bleary and giggling. Then the Magdalen College Choir opens to the pale sky, and sound spills down from the tower like light catching on stone. I remember shivering, hands tucked in my sleeves, as bells folded into voices and the crowd thousands, some still wearing last night’s glitter went strangely still. It’s the kind of moment that makes your hangover sit up straight and listen.

Then the solemn gives way to the silly, as it always does here. Below the bridge the river waits, cold as a dare iced with mist, and the brave or foolish fling themselves in while the rest of us cheer and wince. Once, wandering away with numb toes and a warm paper cup, I felt that odd mix of reverence and mischief: hymns for the sunrise, splashes for the living. It startles you awake to the year equal parts blessing and prank, and somehow that balance feels truer than either alone.

Pints that remember a quiet royalist rebellion

Funny how a sip can taste a little defiant, as if the glass remembers more than it lets on. The room smells of old wood and candle wax, and the low ceiling presses the hush closer, like a hand cupped around a secret.

Between 1642 and 1646, back rooms in Oxford weren’t just for gossip; they quietly filled ranks for the king and passed around propaganda with the ale. Some cellars still keep musket holes pocking the stone, and royal insignias carved into their beams. I once caught my fingertip on one of those rough marks, and the beam felt like it still shouldered its scars.

It surprised me that politics once traveled by pint, but it suits a city where big ideas roam in ordinary clothes. Maybe that’s why the modern brew carries a faint edge, each swallow a small nod to a quieter mutiny. You raise your glass and feel the past lean in, not loud or grand, just steady enough to warm the throat.

Holywell Music Room: Candlelit Classics Since 1748

It feels like a secret hiding in plain sight: a small room where candles tremble and the wood remembers applause. The Holywell Music Room has been doing this for centuries, the oldest purpose built music hall in England, still keeping faith with candlelight and the hush before a bow touches string. I remember glancing at the program and grinning Beethoven on a weekday, as natural and intimate as a neighbor’s voice through a thin wall.

In Oxford, time loosens its collar here. Each week the candles are lit, and instead of buskers you get sonatas drifting through wax scented air, a faint creak in the benches, the kind of silence that feels kind. It’s surprising and beautiful, how an ordinary door opens onto a room that still believes music is a gathering, not a spectacle; I left with that steady, quiet feeling that some traditions aren’t old at all they’re simply alive.

An absurd shark the city learned to love

I still grin at the thought of a quiet street, kettles hissing, and a 25-foot fiberglass shark lodged nose first through a roof, as if a punchline dropped from the clouds. It appeared overnight in 1986, turning breakfast into a small town myth: tiles cracked, jaws open to the sky, birds looping around the fin like they’d discovered a new sky marker.

At first people bristled and wrote letters; then something softened. The shark became the landmark kids used for directions, the neighbor everyone gossiped about and then defended, the odd streak of wonder that made the ordinary feel awake. Even the council, after calling it “absurd but admirable,” eventually granted it heritage status – which, in Oxford, felt less like approval and more like acceptance. I remember standing there and realizing how a place can adopt the unexpected, turning protest into fondness, until what once startled you feels like part of your own good story.

Invisible bells for royals and bishops at Christ Church

I love how in brainy Oxford, a whisper can still rule the room. Behind Christ Church’s show stopping grandeur, there’s the old tale of the Phantom Bellman who tolls invisible bells whenever a royal or a bishop slips from this world. People swear the sound travels like a fine thread through stone and shadow – thin as frost on glass – and for a moment the air tastes of old brass and candle smoke, as if the building itself is holding its breath.

What gets me is that no one goes to hunt down the noise. Superstition beats curiosity here, and somehow that feels right. In a place that measures minds and maps galaxies, they still leave one mystery unprodded, a small bow to the solemn rhythm of endings. I remember thinking it was a gentle kind of courage: to let the unseen have its say, and to accept that, sometimes, the truest bells ring where no hands ever reach.

Memorial to a lost quarter that steadied a university

I remember the hush by the Botanic Garden wall, bees nosing the lavender while the river breeze thinned the noise of the street. A modest stone marks the original Jewish cemetery; it feels like a door left ajar in time, the kind you notice only when the light changes.

Long before 1290, the medieval Jewish quarter here was busy with merchants, lenders, and physicians whose careful ledgers quietly kept the earliest scholars afloat, helping to fund the first life of the university. Then came the expulsion, and the absence still sounds louder than footsteps. In Oxford, that small memorial asks for something simple: a pause, a breath, maybe a moment of thanks for people who helped the beginning, even if their names drifted away.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford

Oxford’s borrowed bridge with a competitive glint

I remember laughing the first time someone called it Venetian. Under the arch, the air was cool and a little chalky, the kind of smell you get from old stone after rain, and footsteps softened as they crossed. Then came the confession: Hertford College’s Bridge of Sighs wasn’t about Venice at all – jealous students wanted one because Cambridge had theirs first, so they simply made their own.

What gets me is the cheek of that move. Even its name is borrowed drama, a theatrical sigh pinned in place above a quiet lane, as if spectacle could be studied like Latin. It feels so Oxford: the city that doesn’t just learn history, it turns footnotes into headlines, answering rivalry with craft. And in that moment, with bells carrying over the rooftops and a breeze catching the scarves of passersby, the copy becomes its own original – not because it’s faithful, but because it’s fearless.

Thousands of cut ties hang across a pub ceiling

First thing I noticed was the hush that comes when everyone looks up at once. At the Bear Inn, the ceiling is crowded with cut tie ends thin colors, club stripes, faded crests glowing in the amber light. When the door opens, they rustle a little, a low slung sky of color swaying above the pints.

It started in the 1950s, when the landlord began snipping the ends from patrons’ ties and tucking them into frames, an invitation to loosen up. Now there are more than five thousand tiny flags from ceiling to bar, with neat labels and lifted corners worn smooth by time. Once, I paused at a frame and spotted a familiar college stripe, and for a moment I felt oddly at home.

What gets me is how playful and kind it feels, the way a city known for gowns and lectures also keeps space for a bit of harmless undoing. In Oxford, you glance up from your pint and see proof that formality can soften without vanishing. Those trimmed ends sit there, row after row, quietly insisting that a good laugh belongs beside good manners.

Where dragons and fauns first drew breath

Funny how the wildest worlds began at a wobbly table. In The Eagle and Child, battered wood tacky with Guinness rings, you can almost hear drafts trading hands Tolkien nudging a dragon into the light, C. S. Lewis smiling as a faun steps out under a lamppost. The room is small, ceilings low, the air carrying that mild mix of polish, hops, and old stories.

Once, sitting there, I caught the soft clink of glasses and felt how ordinary noise can cradle impossible things, like embers catching in a hearth. The Inklings met as friends first, reading aloud, teasing, trimming, letting wonder elbow into the room until Middle earth and Narnia felt suddenly close and real.

That’s what moves me about this corner in Oxford: the reminder that magic doesn’t need ceremony, only company and a table that’s seen a few spills. You look at the dents and sticky rings and think of the courage it takes to share a rough page, and how, over time, those small, stubborn sentences grow up into whole worlds.

Einstein’s black pine whispers in a centuries old garden

I love the feeling of walking into a place that’s been tended since 1621. In Oxford’s Botanic Garden one of the oldest anywhere there’s a quiet surprise tucked behind the gates: a young black pine grown from a cutting of a tree Einstein admired when he came to lecture in 1931. I remember reading the small label and smiling, picturing him pausing there, mind full of galaxies and chalk dust, eyes resting on needles and shade.

The bark looked soot dark, the air held a faint resin sweetness, and the needles made a soft sound when the breeze passed. What moved me most was how gentle the story felt: a brilliant man noticing a tree, and that moment echoing forward as a living branch. It made the garden feel less like a museum and more like a conversation across time a reminder that in this city, wonder grows in quiet corners and keeps on growing.

A rebel’s lantern in the first university museum

I didn’t expect mischief to glow behind glass. There it was: Guy Fawkes’ lantern, the very one from the Gunpowder Plot, sitting almost casually beside smooth Roman faces and the quiet of Egyptian mummies. The room felt cool and muffled, light pooling on pale marble and linen wrapped stillness, as if the air itself knew to keep a secret.

Founded in 1683, the Ashmolean is the world’s first university museum, and in Oxford it wears that history lightly, with a kind of bookish grin. I love how the lantern lives so near the statues and sarcophagi, rebellion and ritual sharing the same hush. That closeness is what surprises you: the past refusing tidy boxes, letting opposites breathe side by side.

I remember thinking how tender it felt to see a would be spark of upheaval resting among gods and pharaohs. It turns history from a distant lecture into something human and complicated, like people do. A quiet reminder that knowledge can hold both wonder and trouble, and still speak in a calm voice.

Exams, balls, dinners Oxford’s wardrobe never takes a day off

The first thing I noticed wasn’t the spires but the sound: a hush of fabric skimming cobbles, like a tide of black silk coming and going. Even on an ordinary afternoon, someone would slip past in an academic gown, threads of embroidery catching a shy gleam of light, cufflinks clicking softly like tiny metronomes. They looked deliciously out of time, as if they’d taken a wrong turn from a candlelit hall and were now, rather elegantly, late for some secret duel.

What I loved most was how the dress codes turned nerves into ritual. Before an exam, the white tie and polished shoes felt like a promise to yourself; at a dinner, the crisp collar softened the day’s edges and made small talk feel warmer. In Oxford, clothing becomes a kind of armor and invitation at once pulling students into a lineage where studying isn’t just brainwork, it’s a ceremony. It made the city feel like a stage set for courage, where the rustle of a gown could steady your heart just enough to walk in and mean it.

On Banbury Road, a dictionary takes shape

It still makes me smile that something as enormous as the Oxford English Dictionary began in an ordinary house, the kind with a squeaky gate and a kettle always just about to sing. You can almost hear the soft thump of envelopes through the letterbox, the rustle of paper like rain against red brick, while editors lean over ink stained slips and the whole room smells faintly of dust and tea. In Oxford, it turned out, a universe of words was coaxed into order at a kitchen table.

What gets me most is how it grew: thousands of handwritten definitions posted in by strangers, each scrawl a little pulse of care. One tireless contributor was writing from an asylum for the criminally insane, proof that language is a wide doorway, not a gate. The dictionary feels, in that light, like a patchwork quilt stitched by unseen hands warmed by generosity, obsession, and the oddities of human life. I remember thinking, if meaning can arrive from anywhere, then perhaps all our rough drafts have a chance to belong.

Where truth is strong and students test its limits

I always smirk at the Latin carved over the chamber: Fortis est veritas Truth is strong. The benches glow with dark, old polish, lamplight settling on their curves, and the air has that paper and rain smell that lingers in places where ideas hang around. From the gallery, a slow hush settles before the first voice rises, the kind that makes you sit up a little straighter without knowing why.

Founded in 1823, the Oxford Union has welcomed everyone from Einstein to Mother Teresa, and it still feels like a stage where sentences walk out wearing their best shoes. You can almost hear the overlap of eras in the woodwork grand declarations, gentle doubts, and the heartbeat thud when a clever line lands.

And here’s the irony that makes me grin: beneath that noble motto, so many future politicians once rehearsed their fibs, testing them like glassware to see which would ring just right. Somehow that contradiction doesn’t cheapen the place; it clarifies it. I left believing that truth’s strength isn’t in volume or victory, but in the way it keeps returning to the mic, steady as breath, while the room learns, slowly, to listen.

Post exam joy the university can’t contain each spring

For a moment I thought winter had wandered back: the air went white as confetti and flour drifted over the old stones, and the breeze smelled faintly of shaving foam. Squeals ricocheted off college walls, ribbons stuck to bikes, and I remember brushing a stripe of foam from my sleeve. In Oxford, they call it Trashing, a spring tradition that erupts the minute exams end. The university discourages it, of course, but crowds of giggles and paper keep returning with the blossom.

What struck me most wasn’t the mess but the permission it seemed to give faces softening, strangers laughing together, shoulders finally dropping. The memos and frowns feel small out there; delight refuses to queue, and it spills onto the cobbles anyway. Between carved libraries and quiet quads, there’s room for mischief, proof that study and celebration can share the same street.

He cycled through pollen with a gas mask.

I can’t help smiling at the image: a thin figure pedaling along buttery lanes, lenses fogging, the rubbery tang of the mask mixing with the green tickle of hedgerows. Not terror, just hay fever – a private battle with spring while the chain hummed its small, faithful song. It’s oddly tender, like a beekeeper moving through blossom, keeping the world’s sting at arm’s length.

I remember biking on a sneezy April and thinking of him, and how in Oxford a bit of eccentric armor feels almost like a second uniform. The same stubborn kindness to one’s own body – I will breathe, I will think – belonged to the mind that would help unravel the Enigma, a lighthouse sweeping patiently for patterns in the dark. It makes you forgive the oddities before anyone asks; you just feel grateful for the strange, practical ways a person protects their brilliance long enough to use it.

Final thought

In the end, it’s not the grand colleges or soaring spires that define Oxford, but the quieter moments that live between them – the echo of footsteps on old stone, the soft light in a library window, the laughter spilling from a hidden café. These are the details that give the city its soul, stitched gently into every street and story. Oxford isn’t just a place of learning, it’s a pulse of memory and wonder that keeps unfolding. And if you listen closely, you can still hear it – the quiet heartbeat of a city forever thinking, dreaming, and alive.