Edinburgh: 30 Strange and Fascinating Tales Beneath the Fog

I like to meet a city by listening for the quiet bits, and in Edinburgh that means turning a well worn book to its margin notes, where the smell of wet stone mingles with a breath of salt on the wind, lamplight pools in windows, and the hush of footsteps follows the rain. Each small thing hints at something I hadn’t noticed before, a story tucked close to everyday life. Nothing grand, just the pauses that make you stop at a doorway or linger on a bridge a little longer. Walk with me through these overlooked details, and we’ll find the deeper spirit that keeps surprising me.

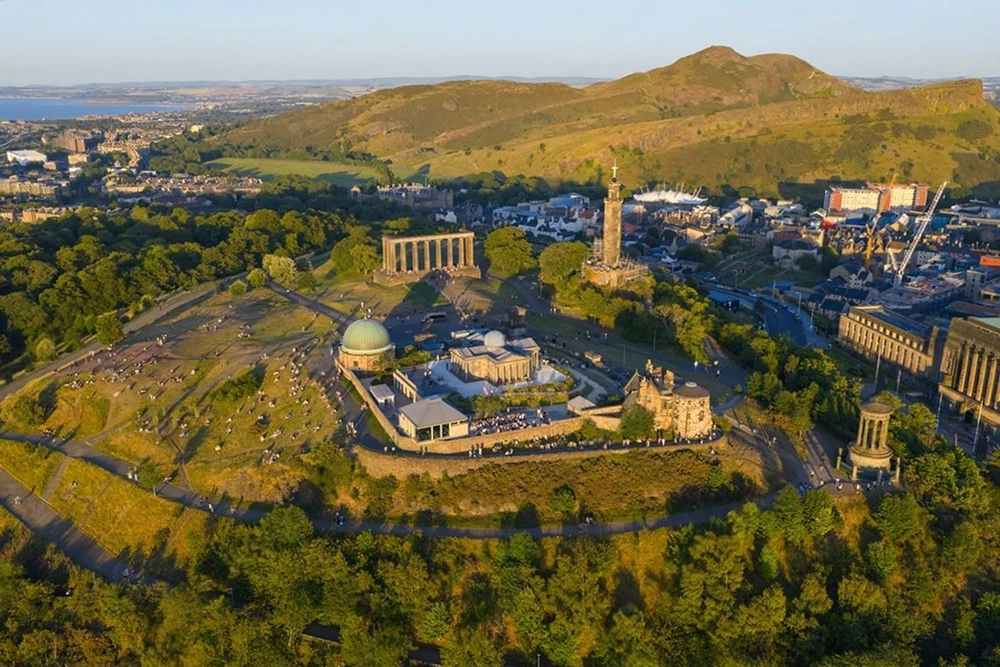

Where a sleeping volcano keeps watch over a city

I still get a shiver when the skyline suddenly rises into black rock and battlements, as if stone had decided to grow a spine. Seven hundred million years of cooled fire hold the castle steady, and it feels ancient in a way that settles the lungs; the wind smells of rain and iron, and the whole ridge throws a slow, brooding shape over Edinburgh. From below, the walls look less like architecture and more like a decision the land once made and never took back a flint in the heart of the city.

Tucked within those big, weathered stones is St. Margaret’s Chapel, small as a held breath and somehow tender. It’s the oldest surviving building in the city, and you can sense it in the quiet the pale walls, the narrow window light, the hush that asks you to stand still. It’s funny how this place once fixed the fates of crowns and banners, yet its oldest room whispers of patience rather than power.

Maybe that’s why the silhouette feels so protective at dusk, when the sky turns slate and the gulls drift like loose scraps of paper. The castle doesn’t just top the hill; it lends the city its mood, that steady, thoughtful weight. I remember walking away thinking how comforting it is to live beside something that ancient like being reminded, gently, that storms pass, stone holds, and stories keep their watch.

Whispers From the Streets Buried Just Beneath Our Feet

I didn't expect the quiet to feel so present. The air is cool and smells of damp stone, and your voice drops to a whisper without meaning to. They call it Mary King's Close, a warren of hidden streets sealed beneath the bustle above.

People tell stories of ghosts down here fleeting figures, footsteps that don't belong and the plague still hangs in the imagination like smoke that never quite cleared. Once, I felt a brush of cold across my wrist and laughed at myself, but it stayed with me, like standing inside a held breath. It is so quiet that the uneven flagstones make you think about names we don't know.

What moved me most wasn't fear; it was tenderness for the lives that once filled these rooms ordinary breakfasts, whispered plans, sudden endings. Places like this remind me that a city isn't only stone and streets; it's the stories that linger, asking us to pay attention. Daylight felt brighter afterward, and I carried an odd gratitude, a small reminder to remember them.

The day a regiment marched with a thirsty elephant

It still makes me smile: behind all that stone and ceremony, their most loyal companion had a trunk and a slow, patient stride. You can almost hear the pipes and feel the cool air on your cheeks, the drumbeat of boots answered by a heavier, gentler thump, as if the whole place decided to keep time with a different kind of heart.

In the 1830s, at Edinburgh Castle, the 78th Highlanders brought back an elephant from Sri Lanka. Local legend says it loved marching with the regiment and even developed a taste for beer in the canteen, its trunk nudging toward a frothy sip while mugs clinked and the room smelled faintly of yeast and boot polish. I remember laughing at the thought of a sergeant sharing his evening with a gray, whiskered face peering in like an old friend.

What gets me is how this story gives history a mischievous grin. A garrison so strict and straight backed somehow made room for something tender, until the fortress itself grew a soft heart. Maybe that’s why the place feels warmer than it looks because once, among orders and oaths, someone shared their march and their beer with a gentle giant.

A nation that chose an untamable unicorn

I still grin at this: Scotland’s official animal is a unicorn, chosen back in 1369 for being fierce and impossible to tame. There’s something stubborn and beautiful about that, like picking a wild compass instead of a map. It tells you what kind of spirit lives here proud, a little mysterious, and unafraid to dream out loud.

In Edinburgh, they’re everywhere if you let your eyes soften rearing from royal coats of arms, peeking from hidden corners of Parliament, glinting in rain dark gold on gates and quietly carved into old stone. I remember the small shock of delight each time one appears, as if the city were winking, reminding you that ordinary days can carry a secret shimmer.

What stays with me is how natural the magic feels, folded into daily life without fuss. The unicorn isn’t just whimsy; it’s a promise to hold onto what refuses to be broken or boxed in. And walking those cool, echoing streets, you can’t help feeling invited to keep a little of that untamable courage for yourself.

From foul lake to the city’s green heart

Hard to believe these soft lawns were once a line of defense. In Princes Street Gardens, the grass hums with bees and the air smells faintly of damp stone and cut roses, yet under all that calm is the memory of Nor Loch – a 42-acre, man made sheet of water drawn to guard the Old Town’s northern edge.

By the 1700s, that protective lake had turned foul. People tipped their waste into it until the surface grew sluggish and dark, and the smell must have hovered for days. From defense to dump – a shift so complete it still makes me blink.

Then the water was drained and the ground slowly planted, and now the eye rests on color and shade instead of scum and threat. I remember sitting there and feeling a quiet, stubborn kind of hope – the way a place can be reclaimed, a scar turned into a garden. It’s the gentlest lesson: safety and beauty don’t have to sit on opposite sides.

The clock that kindly runs three minutes fast

There’s a quiet kindness in a clock that lies. I remember looking up at the Balmoral’s great face in the mist, its hands just ahead of everyone’s footsteps, while the air around Waverley tasted like rain and metal. People moved with that small, purposeful hurry the sort that feels like being taken care of and somewhere a train sighed and the clock chimed as if to say, now. In Edinburgh, even the time seems to have good manners.

It’s been deliberately set three minutes fast since 1902, and somehow it still works; locals treat it like an unofficial alarm, glancing up and adjusting their pace without thinking. I love how a whole city can keep a century old promise just to help strangers make their trains. It turns punctuality into a shared ritual chimes, wet pavement, breath in the cold, and that small buffer between missing and making it.

The first firefighters came with a price tag

I still blink at this bit of history: the world’s first professional fire brigade got its start in 1824, and protection wasn’t automatic. You paid a special insurance tax, and if you didn’t, well… the flames might be left to make their own decisions. There’s something bracing about that honesty, a chill that sneaks in even before the smoke.

I keep picturing damp stone catching the orange flicker, boots ringing on cobbles, brass helmets throwing back the firelight while somewhere a clerk’s list mattered as much as water. Fire feels like a hungry neighbor at the fence, and your name on a register determined whether anyone came to shoo it away. It’s unsettling, but it tells you what a city fears most, and how it chooses to share that fear.

In Edinburgh, that bargain feels like the city itself: practical to the bone, order stitched into the everyday, a kind of care that came with rules. It makes the siren sound different to me now less drama, more promise because it wasn’t always a guarantee. Progress, for all its nobility, sometimes starts with a ledger before it becomes kindness.

The knighted king penguin who leads his own parade

I still grin whenever I think of a penguin wearing medals. Sir Nils Olav waddles past the Norwegian King’s Guard with a gravity that somehow matches the click of their boots, ribbons catching a shard of sun on his sleek black and white chest. There’s the faint, salty tang around the enclosure, a soft drumbeat in the distance, and a ripple of giggles he pretends not to hear, as if dignity were something he was born to wear.

No other zoo on earth gives a bird real rank and a parade, and the delight of it never fades. At Edinburgh Zoo, it feels like the city has knighted a wink stitched into ceremony, letting tradition meet play for a brief, hopeful minute. I remember leaving with my cheeks aching from smiling, amazed that a small, serious waddle could make a whole crowd believe the world is kinder than we expect.

A whole city doubles for art and laughter

I remember how August felt like a key turning in a lock; suddenly the streets hummed, as if the day had borrowed an extra heartbeat. In Edinburgh each August, the biggest arts festival on the planet squeezes itself into those ancient wynds, and you can hear it everywhere: drumbeats bouncing off stone, a trumpet warming up in a basement, a joke breaking into the open like sunlight after rain. The air smells of wet cobbles and chip shop salt, and flyers brush your sleeve like bright confetti, a friendly chaos that somehow makes perfect sense.

What gets me isn’t just the scale, it’s the tenderness of it all. Strangers trade show tips in a drizzle soft queue, then laugh together like old friends in rooms barely bigger than a kitchen. The Fringe turns the city into a playground for courage, where experiments are welcomed, failures are forgiven, and applause travels like a small mercy down the alleys. I left feeling that creativity isn’t a spectacle here so much as a shared pulse – proof that an old place can still surprise you by opening its arms a little wider.

A national monument left beautifully unfinished, still loved

There’s a tender honesty in things that never quite finish. Up on the high ground, twelve Greek columns stand where the money stopped in 1829, and the wind threads itself through them like it’s rehearsing. People once dubbed it “Scotland’s Shame” and “The Disgrace,” but to me it feels more like a poem left mid sentence open, inviting you to lean in and imagine the rest.

What I love is how the city has made peace with it, even found joy in it. Edinburgh spreads out below in a sweep of rooftops and spires, and on festival nights you hear laughter and music drift up around the stone, as if the unfinished edges created extra room for celebration. I remember the light at dusk catching the fluted shafts in soft gold, and realizing how kind imperfection can be: the best views, the warmest gatherings, all framed by a grand idea that never needed to be complete to feel whole.

Where the daily commute wears a novel’s name.

It still makes me smile that the morning rush unfolds beneath a name borrowed from a novel. Waverley is not just a station sign under glass and iron; it’s Sir Walter Scott’s “Waverley,” and, wonderfully, the only train station on earth named for a story. I remember hearing that over the hiss of espresso and the clatter of footsteps, and the platforms suddenly felt like dog eared pages waiting to be turned.

Only in Edinburgh would a commuter hub honor a book so openly, as if the city trusts words to steady the day. There’s something tender in that people late for work, rain freckling the tracks, announcements echoing and yet they pass beneath a title that quietly insists life still makes room for stories. Trains arrive like new paragraphs, and you feel that every journey begins with a small bow to imagination.

Spitting on the Heart of Midlothian for luck

I flinched, then laughed under my breath as a passerby flicked a quick spit onto the little heart set into the cobbles. In the wet shine it looked almost tender, which is strange when you learn that this Heart of Midlothian marks the old tolbooth prison cells, taxes weighed out, sentences read, and sometimes carried through. The mosaic sits there like a scar the city still wears, hard history pressed flat under hurried feet.

In Edinburgh, luck has a stubborn streak. Locals spit on that heart not from malice but from a habit of rebellion, centuries of side‑eye at authority turned into a simple ritual. I remember thinking how human it felt: a crude little gesture that says we’ve seen hard rules and we’ll take our chances anyway. It’s not pretty, but it’s honest and somehow, walking past in the drizzle, it made the street feel braver.

A rogue gate began Edinburgh’s daily penguin parade

There’s a moment each afternoon when the crowd hushes, then breaks into soft laughter the sound of webbed feet pattering over paving like rain finding its rhythm. I remember standing there with a silly grin while a line of penguins waddled past, heads bobbing, the air smelling faintly of damp grass and blooming beds. It felt like the zoo itself exhaled, letting whimsy take the lead.

The best part is how it started: in the 1950s, someone left a gate ajar and one brave bird simply went for a stroll. Instead of panic, they leaned into the calm, and now there’s a gentle ritual a little river of tuxedos making its way around the paths. Every so often a curious wanderer veers into the flower beds, and you can hear a gardener’s resigned chuckle ripple through the onlookers, as if mischief is part of the choreography.

Only in Edinburgh could such an accident mature into a daily kindness, a parade that reminds everyone that order and play can walk side by side. Kids squeal, adults soften, and for a few minutes the world feels both smaller and kinder, as though the city is letting you in on a secret it’s kept for years.

A longer mile made of several streets

I remember smiling at the name the “Royal Mile” isn’t one neat street at all. It’s a string of streets, bead after bead of cobbles, running 1.81 kilometers exactly one Scots mile just a little longer than the English kind, which somehow feels right, as if history measured itself in longer steps.

Between castle and palace, the stones have kept their counsel through coronations, riots, and centuries of intrigue. On a drizzly evening in Edinburgh, the air smells of rain and malt, and voices bounce off the closes; I once lingered there and felt how pomp sits right beside gossip on the same ground. Maybe that’s the secret: this longer mile gives room for everything the ceremony and the whispers, the grand and the everyday to breathe together.

Luck from a bronze nose and a loyal heart

Funny how a small dog can hold a city’s heart. I remember a damp afternoon by the old kirkyard, and there he was: Greyfriars Bobby, a little Skye Terrier cast in bronze, his legend glowing like a small lantern in the mist. Fourteen years he kept watch at his master’s grave – not noisy, not grand, just steady, the way real love tends to be.

They say a gentle rub of Bobby’s nose brings luck. So many hopeful hands believed it that the snout turned bright as a coin wished into a fountain, and after years of devoted polish it even needed repair. I love that detail: affection leaving a shine you can measure.

In Edinburgh, the story doesn’t feel like folklore; it feels close, almost personal. It makes me think that luck sometimes arrives as loyalty remembered, and that a city can choose to keep faith alive simply by touching the same small spot, again and again.

Georgian order beside a wild medieval heart

I love that moment when the streets suddenly align. In Edinburgh, the New Town runs parallel to the medieval jumble of Old Town, a late-18th century Georgian experiment of wide avenues, terraces, and cool neoclassical poise, like graph paper pinned to a hillside. It set the pattern for British urban renewal, proving that order could still make room for life.

Yet the order feels warm at street level. Indie shops glow behind sash windows, bakers and bookshops tucked into crescents, and the stone catches a soft, honeyed light. Behind an iron gate there’s a quiet garden of lilac and lawn, a hush where you can hear your own thoughts. I remember thinking how rare it is for ambition to be this gentle elegant on paper, and still humming with small, local lives.

UNESCO honors a city split between grit and grace.

It still surprises me how a single walk can feel like time changing gears. One minute you’re under soot dark closes and lopsided roofs, the next you’re breathing easier along pale stone crescents and tidy squares. The Old and the New sit side by side in Edinburgh, and UNESCO didn’t just pin a medal on old stones – it recognized the living argument they keep having.

I remember a dusk when the smell of rain on cobbles mingled with a faint chord of bagpipes, and the streets felt full of unfinished sentences. The medieval tangle whispers of guilds, riots, and smoky debates; the Georgian order answers with measured lines and tidy ambition. That contrast isn’t a quarrel so much as two hands clasped – politics rubbing shoulders with poetry, rugged history leaning into planned dreams. Maybe that’s why it moves me: the place shows you that beauty can grow from tension, that a city can hold its scars and its polish and still feel like home.

Sunrise on the city’s quiet, sleeping volcano

There’s a hush before dawn up there, when the grass is damp and the air smells faintly of stone and rain. The skyline stretches wide and you can feel the city starting to yawn awake. Once, I remember a few wild deer standing nearby, steady and unbothered, their antlers like winter branches while the first light slipped over the rooftops. From the summit, sunrise isn’t just a view it feels like the day opening its eyes just for you.

It still surprises me that Arthur’s Seat is an extinct volcano, resting right at the edge of Edinburgh as if the city grew around its knees. Locals swear it’s tied to King Arthur, though no one really knows why, and that bit of mystery fits the place quiet, storied, a little untamed. Maybe that’s why the sunrise there hits different: you stand in the wind with a legend at your back and a bright new day in front, and it feels both ancient and brand new at once.

Every corner wears a pedigree of stone

I love how this place shows off without trying. Even on a quiet morning, with the smell of rain waking the sandstone and the skyline stitched with old chimney pots, you feel it: that soft, steady confidence of a city that knows where it comes from.

Someone once told me there are over 4,500 listed historic buildings here more than Glasgow, Aberdeen, and Dundee combined and I remember just nodding, because of course there are. It’s in the way cornices wink above shopfronts, in the carved dates you catch out of the corner of your eye, in the hush that falls on your steps as if you’ve wandered into a well worn library of stone. Edinburgh doesn’t brag so much as breathe; its history sits at the table with you, ordinary and miraculous at the same time.

What gets me is how that grandeur feels generous, not distant. Practically every street corner holds a little proof that everyday life can be framed by something lasting your morning coffee, a stray laugh, a sudden patch of sunlight made a bit more tender by the knowledge that it’s all happening among elders who’ve seen it all and kept standing.

A world of marbles between old and new

I didn’t expect a staircase to feel like a passport. On the Scotsman Steps, the air has that faint scent of rain and stone, and each tread shows a different mood – mossy green, smoky pink, quiet grey – cool against the ankle, softly veined. Between the thrift of the Old Town and the polished confidence of the New Town, the stairs tiptoe upward in 104 pieces of marble gathered from far off quarries, turning a shortcut into something you want to linger on.

What I love is how ordinary it stays, even as it gathers so many places into one climb. It’s a practical link people hustle through, yet it feels like a small atlas underfoot, reminding you that Edinburgh has always been layered and open, old and new sharing the same weather. I remember pausing on a slab the color of tea with milk, hearing footsteps echo and gulls somewhere above, and thinking how a city can be both humble and grand – every day, just one step at a time.

Auld Reekie wore smoke; the pride never washed off.

It still makes me smile when someone says "Auld Reekie" Old Smoky, with that mix of affection and grit. For centuries, coal smoke curled from thousands of chimneys, the winter air tasting of ash and warm hearths; the soot settled on sandstone and, strangely, guarded it. The smoke stitched itself into the stone, filling tiny pores and helping it last through wind and rain. I remember brushing a palm along a façade and feeling history under my fingertips cool, rough, a little stubborn.

These days the sky over Edinburgh turns clear after rain; you catch coffee and sea salt more than soot, and the buildings look pale and clean again. But the old name lingers, not out of nostalgia so much as honesty a nod to hard years that weathered this place and somehow kept it standing. "Auld Reekie" fits like a scuffed leather jacket the city refuses to throw away: practical, proud, and perfectly itself.

Stone streets hiding over a hundred green havens

It still surprises me how quickly the city’s noise dissolves. One moment there’s bus brakes and shop chatter, the next it’s dappled shade, damp earth, and the easy gossip of birds. I remember the way my shoulders loosened – like taking a deep, leafy breath I didn’t know I needed.

In Edinburgh, there are more than a hundred parks and around half a million trees, which explains how botanical hideaways keep appearing just a few steps from the busiest streets. It feels generous, this mix of stone and green – a place where your errands brush past wildflowers, where history stands under a canopy and softens. Maybe that’s the real charm: the city lets you be busy without making you feel hard, giving you quiet within walking distance of everything.

Where cafés and gravestones shaped a wizarding world

I remember a small table by a fogged up window, the air warm with coffee and wet wool. It makes sense that J.K. Rowling wrote so much of Harry Potter in Edinburgh, because even a quiet café feels busy with ideas spoons clinking like punctuation, rain soft against the glass, and those winding lanes waiting just outside. You can almost hear a sentence beginning in the scrape of a chair, the city nudging you toward a story without trying.

Along Victoria Street, shopfronts glow in confident colors, a cheerful sweep against the gray. In the kirkyard, the tombstone of Thomas Riddell sits quiet, the name stone cold and oddly tender; I felt a shiver that wasn’t just from the wind. In that mix of brightness and hush, you realize the wizarding world didn’t appear out of nowhere it grew from steam, stone, and the hush of old names.

Fifty miles, a rivalry stitched with wit

I always grin when the jokes sharpen after a match. Voices rise over clinking glasses, peat smoke hanging in the rafters, and someone repeats that old line: the east wrote the books, the west built the ships. It’s teasing with a memory of pride in it, the kind that warms you like good whisky on a damp night.

In Edinburgh, the punchlines are worn lightly, but there’s steel in the smile, as if the wind off the Forth keeps it keen. Fifty miles away, the reply rolls back from the Clyde with a deeper laugh and easy swagger. After football, you feel the history hovering behind the banter ink and iron, ledgers and rivets two ways of building a life.

What I love is how it never turns sour. It sounds less like enemies and more like siblings arguing at Sunday dinner each bragging, each teasing, neither wanting the other to vanish. The rivalry keeps the stories bright, and the distance between them small.

Hogmanay: New Year woven with song and luck

Just before midnight, the air goes bright with expectation, as if the night itself is holding its breath. Then someone starts Auld Lang Syne, and voices gather into one familiar swell, the kind of tune that makes strangers feel like old friends. I remember the frost on my coat and the warmth in my chest as the last note hung above the bells.

After the cheers, doors open and the “first footing” begins a gentle ritual of luck delivered with a knock. Once, I was handed a square of buttery shortbread and a small dram that tasted warm and lightly smoky; the room smelled of peat and laughter, wool and winter air. There’s something tender about it, this quiet procession of good wishes, warmth passing like a candle from hand to hand.

What surprised me most was how the new year felt less like a party and more like a promise. In Edinburgh, the night invites you in and reminds you that turning the calendar can be a shared act luck welcomed at the threshold, old songs carried forward, and the year ahead already softened by kindness.

Old minds, young footsteps in ancient quadrangles

I always feel a quiet urgency here. The salt tinged wind tugs at black gowns, and the stone chills your hands as you pass under worn arches; robed students hurry past in every season, crossing centuries old quadrangles with that bracing, changeable weather energy. It’s the kind of place where you catch yourself listening for echoes and realize they belong to the present as much as the past.

Founded in 1582, this university is one of the oldest in the English speaking world, and you can feel that longevity like a steady heartbeat. It has stirred minds from Charles Darwin to Alexander Graham Bell, yet it never feels like a museum; more like a well thumbed page where new notes keep appearing in the margins. What I love is how the past feels friendly, not heavy; even the rush between classes carries a kind of optimism in Edinburgh.

Where candlelight once sparked a city of restless minds

Some nights I swear the air still holds an argument mid sentence. I think about those candlelit lecture halls, the chalk dust and wool coats, philosophers crossing paths with economists and scientists until ideas fizzed like ale in a fresh poured glass. It wasn’t polite; it was alive a mix of bold theories and tender doubts, all of it tugging at the edges of what people thought they knew.

In Edinburgh, you feel that current even in the quiet: the way a café hum can carry a dare to think out loud, how a rain soaked afternoon turns strangers into sparring partners over ethics and art. I remember leaning near a fogged window while two students dismantled a theory with the gentlest of grins, and thinking how kind it is when a place invites you to bring your whole mind to the table.

What surprises me most is how warm it all feels. Curiosity here comes wrapped in a soft, steady confidence, as if the past is a low ember in the hearth enough heat to keep today’s questions glowing without pretending the fire is finished. It leaves you braver, somehow, ready to argue beautifully and listen even better.

A handmade hill bridging the old and the new

It still makes me grin that a hill can be handmade. The Mound looks so assured, linking Old Town to New Town like a quiet spine, yet it’s entirely built raised from around 1.5 million cartloads of earth, all piled into a slope people now take for granted.

I remember standing halfway up while bus brakes sighed and a gull wheeled above, thinking how audacious that is: galleries and museums sitting on top, a crown of art on packed soil. You feel the weight of all that effort under your feet the stubbornness, the faith that something beautiful can rise from dirt.

That’s the part that gets me about Edinburgh: the way ambition lives right alongside the everyday. The air smells a little of rain and stone, traffic hums, and still the hill offers a quieter truth that connection isn’t always found, sometimes it’s made, cartload by cartload, until the city believes it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edinburgh

Shadows keep their stories under old cobbles

It’s funny how a chill can feel like company. Down in those underground alleys and ancient closes, the air smells damp, like stone that remembers everything. On a ghost tour, a guide starts naming the city’s old fears witches accused, grave robbers prowling, restless spirits pacing the seams and the stories cling like mist to your coat. I remember how the lantern light shook a little, as if it were listening too.

People call Edinburgh one of the most haunted places, and I get it; the past isn’t past down there, it’s eye level. You don’t need to believe to feel the hush, that prickle along your neck when a tale lands too close to someone’s real life. It’s not just shivers there’s a tenderness to it, a way of admitting we all leave echoes behind.

What stayed with me wasn’t fear but the feeling of being let in on a secret: the city keeps its hardest stories underfoot, and at night it lets us borrow them. A ghost tour felt less like chasing scares and more like keeping watch, together, over names the daylight forgets. I walked back up to the street feeling oddly lighter, as if remembering the dark had made the night a little kinder.

Where history strolls with myth and steady pride

Some mornings the stone smells damp and clean, the kind of wet that sharpens sound so footsteps feel closer than they are. I remember pausing in a narrow close, listening to the hush between gull cries and pub laughter, and realizing the stories here don’t sit quietly in books they brush past your sleeve. In Edinburgh, myth and rebellion swap conspiratorial looks, and that stubborn pride rises like chimney smoke, soft and constant, no matter the weather.

What gets me is how it keeps catching you off guard. An old neighbor tells a tale you’ve never heard, a carved thistle you’ve passed a hundred times suddenly winks in the slant of late sun, and you feel history walking beside you, elbow to elbow. Even the people who grew up here seem happily ambushed by it, as if the city is a tune you can’t stop humming but it keeps adding a new verse just when you think you know the melody.

Final thought

All along, it’s the hidden stories, the small details, the human moments the way a doorway is worn by countless hands, or a laugh lingers in a narrow close that show a truer side of Edinburgh. The city feels like a well loved book whose margins keep filling with notes, each scribble reminding us that meaning lives in the in between. Pause for the quiet and honor the ordinary, and you’ll start to notice more than before. Step onward with a gentler gaze, ready to look closer and be moved.